Why Learn About Web Accessibility

Screen Readers: An Introduction

Contents

When addressing accessibility, a main focus is to make web content compatible with screen readers (often used by people who are blind to access their computer, device, and the Web). That’s not to say that people with other types of disabilities don’t encounter barriers, but this group will certainly face the most barriers given the visual nature of the Web. Often, addressing screen reader compatibility issues will help resolve potential barriers for others as well.

Here we focus specifically on the ChromeVox screen reader add-on for the Chrome web browser because of its simplicity, good support for standards, and its availability across platforms as free, open-source software. We will first introduce you to a number of other screen readers before spending some time learning to use ChromeVox and to experience barriers firsthand.

For new or inexperienced users, learning to operate a screen reader can be difficult, particularly if you are not using one on a regular basis. Memorizing the basic commands provided in the upcoming pages is often enough for screen reader testing purposes, though there is much more functionality in screen readers that is not discussed here. You are encouraged to explore the full range of features that screen readers have to offer as time allows.

ChromeVox is ideal for introducing screen readers, though it does have its limitations, and people who are blind are more likely to use one of the more broadly used screen readers like JAWS, Window Eyes (now discontinued), NVDA, or VoiceOver. What may seem accessible with ChromeVox may not be accessible when using other screen readers.

Summary of Available Screen Readers

There are a variety of screen readers available for different operating systems, whether you are using Windows, Mac, Linux, iOS, or Android, and there are also a few web-based screen readers. The more common screen readers are listed below for reference.

Screen readers should not be confused with text-to-speech (TTS) applications. Though both read text content aloud, TTS only reads content text, such as the text on this web page. Screen readers read content text, but they also read aloud elements of the browser’s interface and the operating system, as well as providing ways to navigate the content, with features for listing headings, links, or tables, for example. These features are not typically found in TTS applications.

Windows (Commercial)

Windows (Free Open Source)

(In addition to ChromeVox, you may also want to install and experiment with NVDA.)

Mac

(To toggle VoiceOver on and off, press Command + F5.)

Linux (Free Open Source)

iOS

Android (Free Open Source)

Browser-Based (Free Open Source)

For a more thorough list of screen readers, see Wikipedia’s Screen Reader entry.

Screen Reader Usage Trends

It is not typically feasible to test with every screen reader available, so it is a good idea to choose the screen readers you use strategically. Understanding screen reader usage patterns can help you decide which one(s) to test with.

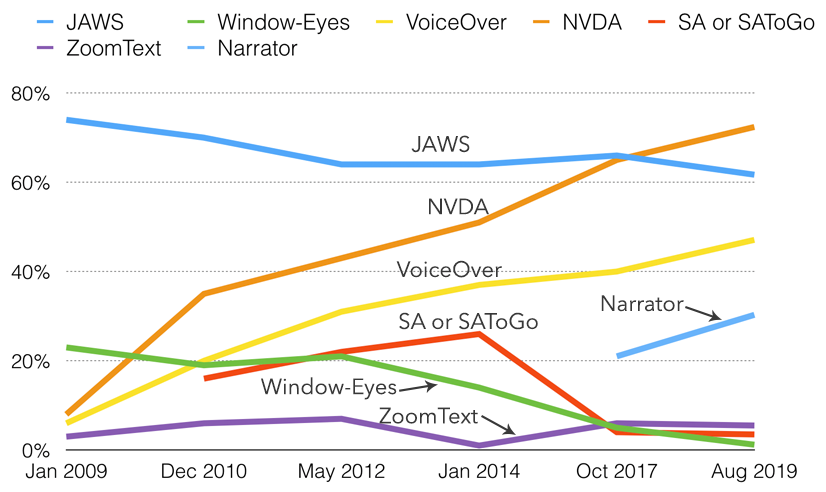

The WebAIM Screen Reader User Survey, conducted every one to two years since 2009, shows changing trends in screen reader usage. Up until the 2019 survey, the JAWS screen reader was the most commonly used. With built-in screen readers like VoiceOver on Mac and Narrator on Windows, and free open source screen readers like NVDA — each much improved in recent years — many users are opting for these less expensive options. JAWS, though highly functional, is expensive software and can be out of reach for some who need screen reader technology. In the 2019 survey NVDA users (72.4%) surpassed JAWS users (61.7%) for the first time. Mac’s VoiceOver users (47.1%) also increased since the 2017 survey (39.6%), as did Narrator users (30.3%) compared with users reporting in 2017 (21.4%). See the latest WebAIM Screen Reader User Survey for the latest statistics.

Mobile screen reader usage has increased exponentially over the last few years, from just 12% in 2009 to 88% in 2017, increasing again in 2019 to 96.5% — keep this in mind when screen reader testing. Testing with mobile screen readers should be considered.

The following table and graph from WebAIM shows usage statistics for screen readers commonly used for desktop and laptop computers.

| Screen Reader | % of Respondents |

| NVDA | 72.4% |

| JAWS | 61.7% |

| VoiceOver | 47.1% |

| ZoomText | 5.5% |

| Window-Eyes | 1.2% |

| System Access or System Access To Go | 3.5% |

| ChromeVox | 4.7% |

| Narrator | 30.3% |

| Other | 6.0% |

Figure: Screen readers commonly used, usage patterns in 2019