Module 2: Anti-Indigenous Racism

Self-Advocacy

Self-Advocacy

Responsibility for blunting racist, sexist, homophobic, ableist thoughts and actions is shared between individuals, organizations, and society. The aim of these modules is to gain knowledge, awareness and skills that will enable learners to take effective actions that combat discrimination and create more inclusive and safe environments, so the experience of learning is a rich one with opportunities for you bring your full creative self too and be meaningfully engaged. It is acknowledged that the power dynamics between the student who may be experiencing or witnessing discrimination and the perpetrators who may be in a position of authority or status (this can also be another peer) can make challenging or speaking up difficult and sometimes scary. There are different factors that weigh into a person’s decision to act and are not always clear-cut reasons nor are they the same for everyone. Whatever the reason, the decision you make should be one that you are comfortable with.

Being informed about the options available to you can help you to determine how you wish to respond and the steps that can be taken, the supports available and the possible outcomes. In some circumstances, the decision to address concerns and incidents does not rest with only you. Once a disclosure is made, processes to respond to situations of discrimination or harassment are triggered such as an investigation or duty to report and respond, as impacts can go beyond individuals directly involved impacting the large group or organization.

Deciding how to respond does not have to be a decision you make on your own and without support. You are encouraged to reach out to program faculty and staff within your institution. There may also be a variety of campus services from which you can also seek advice, will assist you with getting connected to the proper supports and bringing a complaint forward. Remember you do not have to handle things on your own.

So far, we have discussed the government’s assimilative policies and their consequences for Indigenous persons and communities. Scroll through the images by Winnipeg-based artist K.C. Adams titled Perception. The photos prompt the viewer to “look again.”

By juxtaposing these images, Adams evokes the “before” and “after” transformations typical of makeovers. But, in this case, the roles are reversed – the observer undergoes transformation and not the individuals serialized. By focusing on facial expressions, Adams explores the White gaze and how Indigenous persons are misperceived as lazy, addicts, criminals or promiscuous. But a shift in attitudes and perceptions is neither instantaneous nor guaranteed. It requires intentionality and concrete action because reconciliation is an ongoing process of acknowledgement of injustice, reparations and reimagining settler-Indigenous relations. What might this look like in practice?

Revisiting Geronimo and the White Settler Gaze

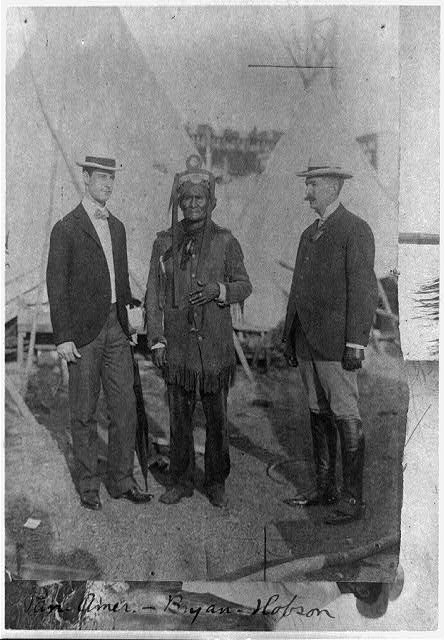

We began this module with the image of Geronimo and the White settler gaze. Look again at Geronimo.

Step 1. Look backward

Make visible knowledge and experience that has been made invisible through selective curricula and media representations. Narratives like Susanna Moodie in Roughing it in the Bush commonly depict Indigenous men as having “coarse and repulsive features” and “intellectual capacities scarcely developed” (qtd. in Simpson 98). The racialization of Indigenous peoples by dominant groups, in this case White settlers, explains the indignities that Geronimo experienced. Geronimo was an Apache warrior who participated in American Indian wars in the 1870s and 1880s before his capture in 1886. As a prisoner of war, he was displayed trophy-like at expositions such as the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo in 1901 (see Figure 2.1 below), where he was made a curiosity for spectators to gaze and gawk at, and was among the main attractions (Swensen 451). Therefore, looking backward involves learning about history and setting aside preconceived notions. This requires actively seeking out Indigenous narratives that explore themes of dispossession and resistance, and a willingness to admit biases and misconceptions.

Step 2. Look outward

Look outward by engaging with multiple perspectives, including forms of knowledge and experiences that have historically been silenced. In this case, for example, listen to the poem When I was in Las Vegas and Saw a Warhol Painting of Geronimo by b: william bearhart, a descendant of the St. Croix Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin and introduced by Padraig O’Tuama. Click to listen.

Step 3. Look inward

Look inward and recognize your positionality and how it shapes your perceptions and engagement with Indigenous peoples. Looking inward is needed to shake off White supremacy and paternalism that lulls non-Indigenous people into thinking that reconciliation begins and ends with a recognition of past injustice and an apology. In other words, one must check any superficial acknowledgement that land was stolen, children were abused, social structures were disrupted, culture was denied, treaties were not respected, and then still go on to say something along the lines of “We meant well. We tried our best. Progress is inevitable, and while it is regretful, you [Indigenous peoples] didn’t have the intelligence or fortitude to be successful. That’s life. Maybe we’ll try to be nicer and help more” (Simpson 100).

Watch the video, Advice for White Indigenous activists in Australia, by Professor Foley of the Gumbainggir nation in Australia.

Step 4. Look forward

This is an ongoing process that begins with learning and sharing while demanding humility. The knowledge that has been introduced to you in this module serves as the first step towards Indigenous awareness. Looking forward with the bits of knowledge you gained and your journey around Truth and Reconciliation, it’s important to think about your responsibilities with added awareness.

- Be cautious of White Saviour Syndrome or being an “Indigenous expert.” It’s important to dispel any assumption that Indigenous peoples are incapable of advocating for themselves, which is at the core of White savourism and rooted in White Supremacy. As non-Indigenous people, we must not take up space speaking on behalf of them. Even the most well-intentioned displays of allyship often centre White and non-Indigenous perspectives.

- SHARE, SHARE, SHARE. Contemplate how this knowledge informs your actions moving forward and share generously with others. The awareness and knowledge gained from this module reflects some foundational Indigenous awareness. This knowledge is critical to your own personal growth, self-awareness and respectful engagement with Indigenous communities. Freely sharing this knowledge will contribute to moving forward in everyone’s Indigenous awareness.

Step 5. Take action

Looking in these ways provides the basis for action and authentic allyship. Completing these Pressbooks is the beginning of learning and unlearning. Doing further reading and increasing awareness, reading the Truth and Reconciliation at Ryerson in the 2018 community consultation summary report could be a first step.

You can start here! Amy Desjarlais (Lead, Kiwenitawi-kiwin Kiskino-hamatewina (Rebirthed Teachings) Working Group) has prepared resources and calls to action for non-Indigenous folks to stand in solidarity with Indigenous folks, residential school survivors and their families.