Chapter 5 – Gastrointestinal System

Abdomen – Inspection

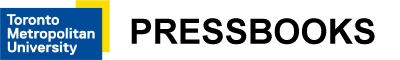

Inspection of the abdomen provides information about the client’s GI system, particularly the intestines, as well as the liver and the abdominal cavity overall. Refer to Figure 5.4 for the quadrants and regions: a horizontal and a vertical imaginary line bisects the umbilicus to help you visualize the four quadrants. Note any abnormalities of the abdomen using these quadrants and regions.

Figure 5.4: Abdominal quadrants

Inspecting the abdomen involves the following steps:

1. Before inspecting the abdomen, note the client’s level of consciousness, facial expression, and assess for the presence of jaundice.

- Clients are usually alert with a relaxed expression, although some may be nervous/anxious. Be attentive to any non-verbal signs of pain such as grimacing or , and continue to observe the client’s expression throughout the assessment. In addition to providing information about non-verbal signs of pain, this can also sometimes help you assess whether further support or guidance is needed.

- Jaundice is associated with high levels of bilirubin in the blood. It is included in the abdominal assessment because it can be associated with diseases of the liver, pancreas, gallbladder, and bile duct. Clients with jaundice have a yellowish discolouration of the and sometimes the skin. An inclusive approach to evaluating jaundice is to inspect the sclera of the eyes, because the melanin in skin influences how jaundice appears. Clients with lighter skin may have yellow discolouration of the skin beginning in the face and transmitting to the rest of the body, but relying on assessment of the skin alone is an example of how health assessment practices can be non-inclusive or racist.

2. Ask the client to expose their abdomen so you can observe from the epigastric (inferior to xiphoid process) down to the hypogastric region (superior to the pubic bone).

3. Note any stoma bags, tubes, drains, incisions, scarring, dressings, or medical equipment (e.g., monitors). NOTE: If you observe discharge/bleeding on a dressing, outline it with a marker/pen and observe whether it increases in size. However, if there is a significant quantity, you should investigate the cause and perform a primary survey.

4. Use and observe all four quadrants.

- Observe the profile view (side view) while standing on the client’s right side. Standing on this side will help you visualize any peristaltic movement, which will move away from you. These movements are the waves caused by the gastrointestinal tract (e.g., large intestine contractions). Peristalsis movement is usually not observable on the abdomen. You may see it in a client who is thin; otherwise, visible peristalsis is a cue that should act as a concern and can suggest an intestinal blockage. In a newborn, observable peristalsis may be associated with pyloric stenosis (narrowing of the opening between the stomach and the intestines), but this condition is associated with other symptoms such as projectile vomiting.

- Next, position yourself so that your eyes are at about the level of the abdomen at the side, and also view the abdomen from the end of the bed. This will allow a full view of the abdomen so you can compare the left and right sides of the full abdomen (including the umbilicus) and assess symmetry. Tangential lighting will highlight any protrusions like a lump/mass.

5. Note any potential signs of observable pain. (Remember: if you suspect pain, always ask the client.)

- Observe for signs of pain may include facial expressions, behavioural changes (e.g., complete stillness or restlessness or guarding) or physiological changes (e.g., holding their breath, shallow breathing).

- In pre-verbal children (or other non-verbal clients), signs of pain may include groaning, grimacing, shallow breathing, irregular rhythm of breathing, and tachypnea. Newborns and infants may flex their hips and knees, moving their legs up to their chest.

- Note that a client may be experiencing pain even if you do not observe signs of it. Clients with chronic pain often do not exhibit behavioural signs of pain.

6. Note the abdominal shape.

- Identify the presence of symmetry or asymmetry and any bulging.

- The abdomen should be symmetrical and the umbilicus should be midline. Note the location of any asymmetry. If you suspect asymmetry, you can ask the client to take a deep breath in and out; this can accentuate any asymmetry or potential bulges. If the client is able to, you can also ask them to hold their head and upper shoulder area off the bed (like a little sit-up) or onto their elbows as this maneuver can accentuate any asymmetry or bulges. You could also ask them to cough; this can increase the intra-abdominal pressure and accentuate a hernia if present.

- If you observe any bulging, further assess the area and note the location. Inspect the umbilicus for bulging, which can sometimes appear as an everted umbilicus. Normally, an umbilicus is inverted. Although an everted umbilicus can be normal, so always inquire if it is new. If you observe bulging, ask the client if they have noticed it, when it began, whether they know what it is, and ask about any associated pain. At the end of the overall inspection, you can gently palpate it to assess its consistency (soft or hard) and the presence of pain.

- Identify the contour (i.e., the abdominal curve).

- The normal contour of the abdomen is typically flat or rounded.

- A concave contour (inward curve of the abdomen that looks sunken in) is concerning because it can be associated with dehydration and malnutrition, and sometimes with anorexia nervosa and cancer. In newborns, it can also suggest a congenital anomaly in which the abdominal contents have shifted elsewhere, such as up into the thorax.

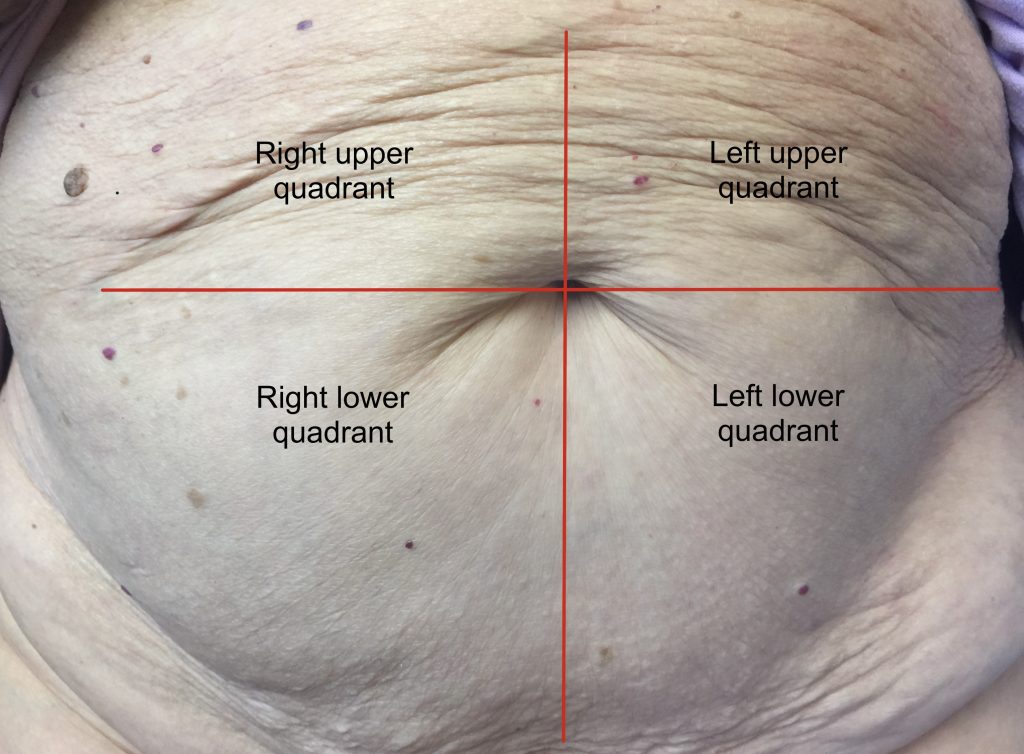

- A distended abdomen is an enhanced outward contour, which can have many causes. See Figure 5.5.

- The outward contour of the abdomen is typically enhanced when a client has increased air, fluid, and/or content inside the intestines, or outside the intestines within the . Distension may be associated with constipation, bowel obstruction, or irritable bowel syndrome. Severe malnutrition associated with protein deficiency and water retention can also distend the abdomen so it looks bloated. Another cause is ascites, which is the accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity. Ascites has many causes, but most commonly liver cirrhosis associated with hepatitis or chronic alcohol use. In rare cases, a tumor might cause distension. Keep in mind that an infant normally has a protuberant abdomen that sticks out because of muscles that are not developed – don’t confuse this with distension. A distended abdomen is firm to touch.

7. Note skin colour, discolouration, integrity, and swelling.

- Skin colour varies based on a client’s racial background and should be consistent across the abdomen and the umbilicus. If you observe a discolouration (e.g., redness), describe it and the location. No swelling should be present and the skin should be intact; describe and note the location of any swelling or damaged skin (e.g., an open ulcer). Examine the umbilicus, which may become infected from a piercing. Note any scars, which may indicate past surgeries.

8. Note the presence of peristaltic movement.

9. Note the findings.

- Normal findings might be documented as: “Abdomen flat, symmetrical with no bulging, swelling, discolouration. Skin intact.”

- Abnormal findings might be documented as: “Client grimacing with shallow irregular breathing. Abdomen distended.”

Figure 5.5: Abdominal distention (By James Heilman, MD – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15335623)

Priorities of Care

Signs associated with an intestinal blockage is a priority of care because it may indicate the need for surgical intervention. Pain, constipation, vomiting, and abdominal distention are possible signs of a blockage. If any are present, notify the physician/nurse practitioner after performing a primary survey with a complete set of vital signs and a full abdominal assessment. It is especially important to auscultate and palpate the abdomen, because absent bowel sounds or a distended/firm and painful abdomen are associated with blockages.

All abnormal signs observed upon inspection require a full abdominal assessment. If you observe signs of pain, begin with a subjective assessment. Any asymmetry, bulging, abnormal contour, swelling, and lesions should be reported to the physician/nurse practitioner.

Activity: Check Your Understanding

refers to tense abdominal muscles as a result of nervousness, pain, cold room temperature or hands of the nurse, or ticklishness.

is the white part of the eye.

refers to use of a penlight directed from the side as opposed to direct light at a 90 degree angle.

is the potential space in between the parietal peritoneum (a membrane which surrounds the abdominal cavity) and the visceral peritoneum (a membranes which surrounds the abdominal organs).